A Vision For Corvallis' Streets

When I first moved to Corvallis, I was extremely excited to join a small city that consistently ranks in the top cities for bike mode share with a bike score ratings that earns it the 36th spot among cities (of all sizes) in the USA. Corvallis must be doing something right to motivate this level of use, right? After spending a few years here with no car and my bike as my primary mode of transportation, I think the story is a bit more complicated than that.

Corvallis is a compact city, meaning that if you can afford to live within the city limits (which is not a given considering the median home price of $526,000), you are likely not far from any corner of the city. In addition, much of the central suburbs of Corvallis are quiet, 25 mph roads where kids can play in the street and biking feels safe. If your commute is primarily within these suburbs – and many commutes that lead to Oregon State University are – then your bike commute probably feels comfortable, at least by North American biking standards (you will still see plenty of high-vis vests though, an indication that not all feel the safety). These facts, combined with the strong pro-biking culture of the Pacific Northwest, probably lead to the high ratings of Corvallis on city bike scores.

However, the high bike mode share in Corvallis happens despite the infrastructure, not because of it. The best bike infrastructure you are going to get in Corvallis, on normal commuter routes, are bike gutters and sharrows, sometimes combined with the extremely lofty designation of “neighborhood bikeway” (which really just means a sign and pavement markings were installed). Ray Delahanty, producer of the CityNerd YouTube channel, had this to say about Corvallis:

It is a little puzzling because the bike infrastructure isn’t exactly world class. It kind of goes to show how important culture and habit are for transportation choices.

Though I applaud the culture of the region that leads to this, it is a shame, really, that bike infrastructure still goes neglected in a city with such a large bike mode share; think of how many more people could be encouraged to bike with a little infrastructure investment!

While it would be great if every neighborhood had a dedicated, grade separated bikeway that followed major travel routes, I think there is some major problem areas that need addressing first. While there are plenty 35 mph, 5-lane stroads to be fixed, perhaps none are more alarming and visible than the SW 3rd and SW 4th streets, which are the two separate one-way pieces of the Oregon State Route 99W alignment as it slices through Corvallis’ central business district. If one wants to bike anywhere in downtown Corvallis, SW 3rd and 4th streets form massive obstacles, each with 3 lanes of one-way traffic and two lanes of parking (that makes 10 lanes for one highway in downtown Corvallis), with a 51-foot-wide traffic area that encourages speeds much higher than the posted 25 mph.

My goal here is to present a new vision for SW 3rd and 4th streets, one that distributes land use more fairly and accounts for the large amount of non-vehicular mode share that Corvallis is fortunate enough to have. Further, this vision will be achievable within the next few years, with few actual changes to the road surface or alignment itself and for a price that is orders of magnitude less than what is typically spent on road repair (e.g., $85.1 million spent on replacing the Van Buren bridge ).

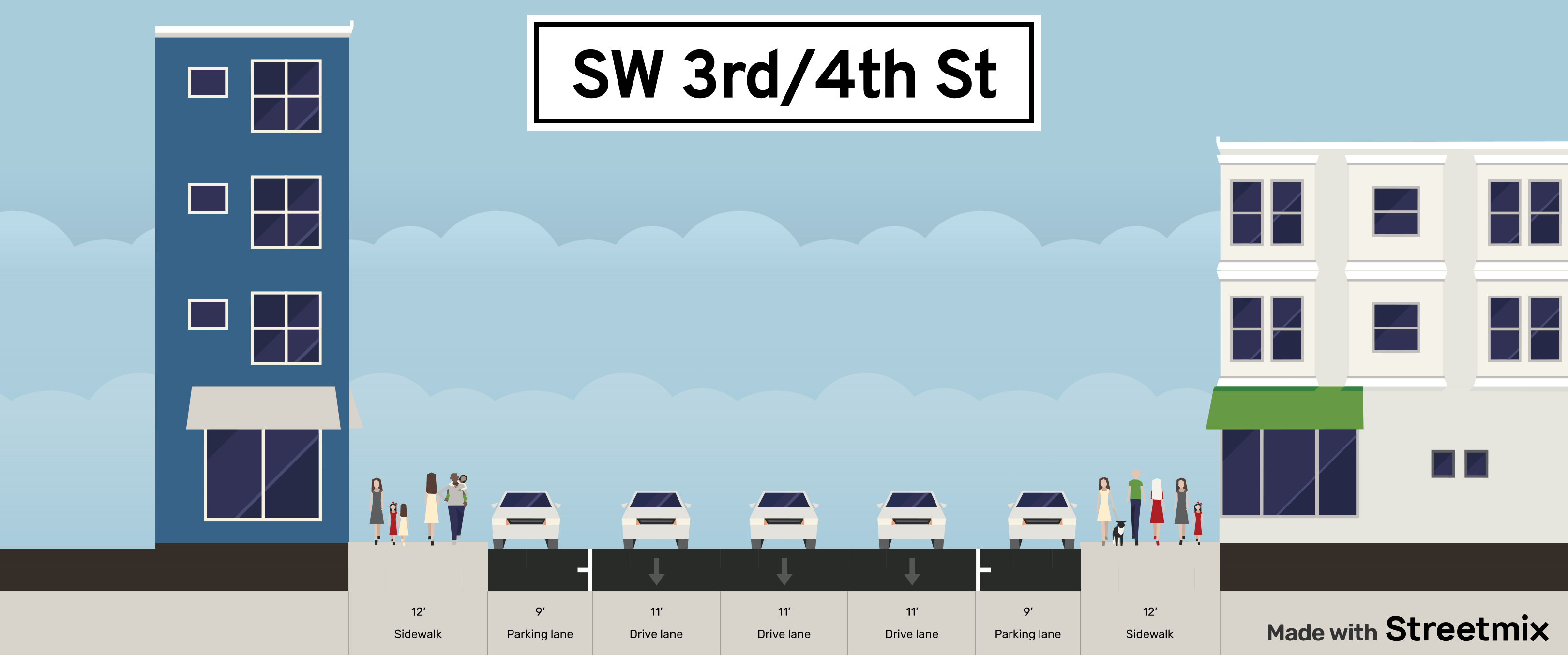

The first step is to determine the current across-road space utilization. Each road, SW 3rd and 4th streets, has the same space usage: three one-way travel lanes with two lanes of curb parking. Based on measurements made on Google Maps, I believe that each travel lane is 11 feet wide, each parking lane is 9 feet wide, and each sidewalk is 12 feet wide, bringing the total roadway width to 75 feet (none of which is dedicated to bikers, who, again make up 10% of the Corvallis mode share). We can view what the current and reimagined streets will look like using Streetmix, a tool for visualizing road design that I first learned about from an excellent video about street redesign on the YouTube page City Beautiful, a channel ran by Dr. Dave Amos. The current state of SW 3rd and 4th streets, as described in this paragraph, is shown here:

This street design prioritizes car traffic over all else, and the experience in downtown reflects it. Being a pedestrian on these streets is not a good experience – as the saying goes, cities aren’t loud, cars are loud, and this street is no exception. Speeds often exceed the posted 25 mph speed limit, as can be expected for such a wide road. Consider what message this sends to visitors of downtown: you are expected to arrive in a car, walk (a probably short distance) to your destination, then return to your car and leave. This, rather than just being accepted as the status quo, should be viewed as reinforcing a specific, preferred mode of transportation.

The alternative is a world where all can feel empowered to choose their preferred mode of transportation. Of course, since so much area has been devoted to cars it can feel like something is being taken away when changes are proposed. But I choose this wording to encourage a reframing where, rather than something being lost by some, something is being gained by all: the freedom to move how we want. It is not a zero-sum game, and there’s room for us all to exist and move together.

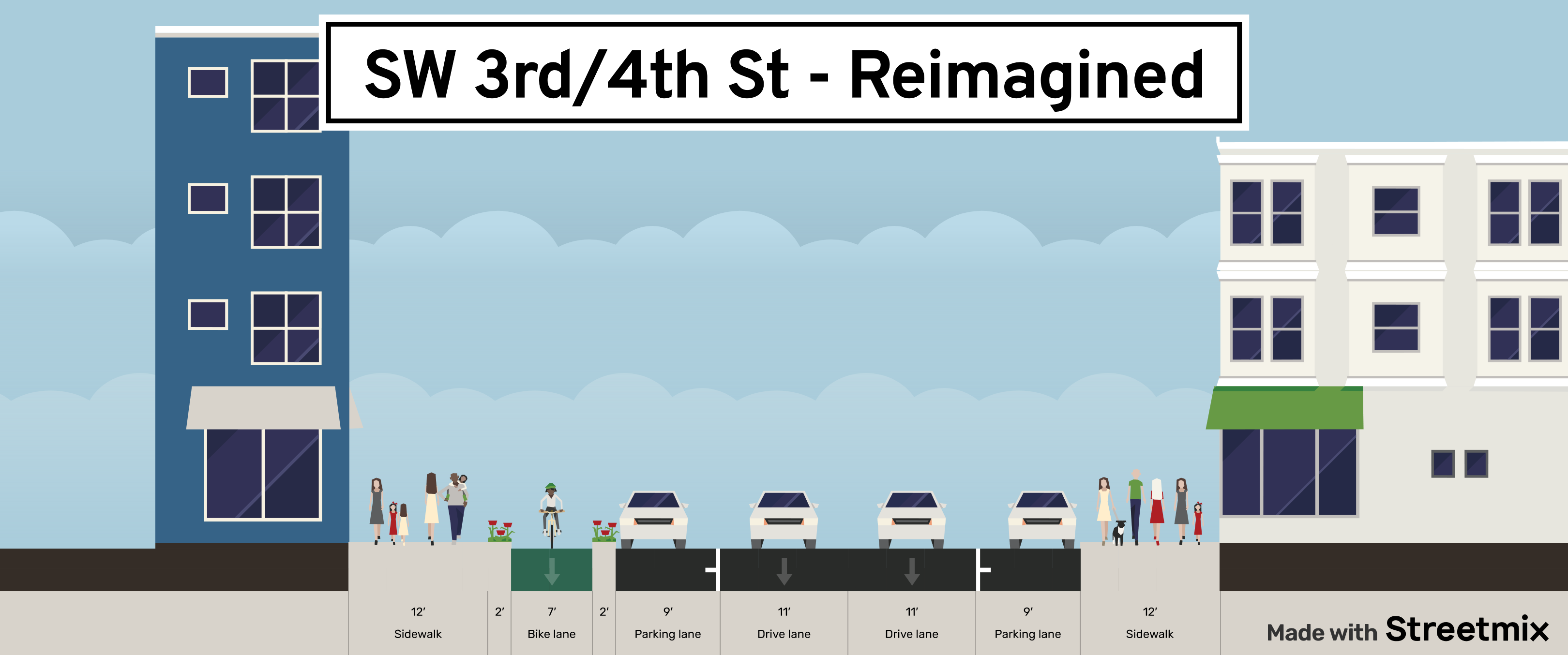

To that end, taking just one driving lane away from SW 3rd and 4th streets would go a long way towards providing a more equitable transportation space. The parking lane would be moved to the previous driving lane and the driving lane would be replaced with a bike lane, separated from parking and pedestrian traffic by a curb. An example of what SW 3rd and 4th streets could look like is shown here:

This is a road that all can feel welcome on, despite their transportation choices. Having such a road greet visitors and residents alike to downtown Corvallis will show all that they have a safe way to move in the city and go a long way to showing that good cycling infrastructure is good infrastructure for all, pedestrians and drivers included.

There are always concerns whenever there are changes from the status quo. Typical concerns of the installation of bike lanes (ignoring obviously bad faith talking points) are from business owners worried about how traffic changes will impact their businesses and from drivers worried about increased traffic due to losing driving lanes. We need look no further than a very similar city a bit south for a case study: Davis, California, home of UC Davis (and number one on the USA bike mode share rankings). In 2016, Davis conducted a road diet on 5th street, eliminating a driving lane from most of the alignment. This transformation can be seen on Google street view:

A case study of this road diet found that the number of bicyclists on 5th street over tripled while actually decreasing driving times a statistically significant amount. This is a common story with road diets; resistance from the loudest drivers often assumes that travel times will increase, while the actual evidence shows that they have little to no effect on travel times. Similarly, improving bicyclist and pedestrian infrastructure has been found in many studies throughout the USA to have either positive or negligible economic impacts to local businesses.

There are massive benefits and few drawbacks to improving bike infrastructure, and the suggestion here to do so involves very little spending – it could be as simple as bolting down some concrete parking dividers just to start. So, the question, then, is why isn’t anything being done to support the over 10% of citizens who bike to work (not to mention all the other bike uses)? My opinion is that there is an over reliance on the public feedback process in street redesigns and a lack of vision in leadership. Perhaps that is a story for a future blog, though.

For now, I leave you with a vision for a downtown that would measurably improve the experience of moving for your neighbors and even, perhaps, for you too. Freedom is deserved for all and includes the freedom to feel safe while using your preferred mode of transportation. Street design is a reflection of a city’s priorities, and shouldn’t it be the case that a top-3 bike city should be setting the standard for all to follow? If we start to build better bike infrastructure, Corvallis might even be coming for the top spot, Davis!